Lesson

Photo Credit: Mart Production on Pexels.

Analyze the historical events that led to contemporary attitudes towards waste and throw-away culture through a collection of book excerpts, articles, and other publications, and develop a potential future outcome for an end to the culture of disposability.

Grades 9 and up

Time Needed 2-3 weeks

Materials

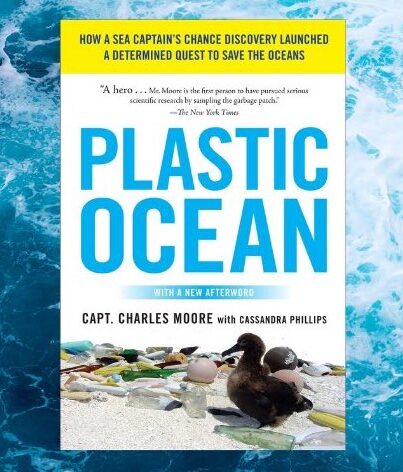

Copy of core text: Plastic Ocean by Captain Charles Moore, Chapter 6

Cross reference texts:

- The World Is Drowning in Plastic. Here’s How It All Started | WIRED

- The History of Plastic: The Invention of Throwaway Living | Dieline – Design, Branding & Packaging Inspiration (thedieline.com)

- Why our throwaway culture has to end | National Geographic

- ‘Throwaway Living’: When Tossing Out Everything Was All the Rage – Plastic Waste Solutions | Dr. Ross Headifer (includes links for additional research)

This lesson was created by high school and university English Language Arts instructor Sarah King and is part of the “Plastic Ocean” English Language Arts Toolkit.

This lesson plan functions as a unit that may also be paired with the lesson titled “Plastic Soup in a Brave New World.”

Purpose and Context

A text that references events and places from the reader’s life is relatable. The challenge for every teacher in every subject is to present valuable information in a relatable way so students may accept its relevance and validity. The opportunity to read and discuss Captain Moore’s Plastic Ocean Chapter 6, “The Invention of Throwaway Living” provides an experience for learners in a variety of academic subjects to explore an historical timeline including events that specifically mark the beginning of the Age of Disposability. As a Language Arts teacher, my interest in writing this lesson plan is rooted in cross-curricular opportunities with social studies, the sciences, and current events, but the direct connection Moore makes on page 101 with Wades Dairy Farm in my home state, Connecticut, caught my attention in a deeper way. Such a specific connection succeeded in capturing my attention, and the goal of this lesson is to incorporate a variety of texts, internet sources, and classroom activities to guide students toward an awareness of how significant events from the past are affecting the present and their future. Students will identify specific events on a timeline they create beginning before they were born with a focus on how these events signify the era of throwaway living which continues today. By evaluating the past, students will gain insights into the corporate decisions and economic motives that have driven plastic production to the crisis it now is and continues to be. While Chapter 6 provides several references to specific events and inventions that generated this crisis in the past, students are asked to consider what events are happening currently that indicate the continuation of plastic pollution and/or efforts to change the trajectory. Additionally, students will gather evidence to theorize about the potential for the cycle to end as they anticipate an actual date on their timeline when this could happen since Captain Moore concludes Chapter 6 with an optimistic proposal. Moore asks, “What if a preconceived endgame for each thing we made or bought was the rule, not the exception? If we had such a plan, then plastics as a material, valued so little and disposed so readily, would be rehabilitated… Without an endgame, it all becomes mere waste, and waste is worthless” (108). This challenge to change the habits of the past is directed at future generations as Moore admits in his opening “Note to the Reader” his wish he had noticed the plastic pollution crisis sooner as he dedicates Plastic Ocean “To the generations, not yet born, that creates a world where plastic pollution is unthinkable.” This hope for the future and potential for change is an exciting possibility that may only happen if we commit to learning the facts about single-use plastics.

Group discussions generated by the extended texts are a significant part of this lesson as students are encouraged to make connections between their own interactions with plastics and the research they are reading about current efforts to improve awareness, increase recycling, and create alternative plastic-free products. The motive driving Captain Moore’s passion for ending the plastic pollution crisis is as deep as the ocean since he explains, “This story has never been only about plastics. It’s about an epic shift from austerity and frugality to abundance and profligacy. When struggle was still the norm, inspirational texts- from the New Testament to Ben Franklin’s Poor Richard’s Almanac- preached thrift and simplicity” (97). Consumerism is central to throwaway living and while struggle remains a societal norm, especially in this era of pandemic, Moore identifies the human need to thrive with sustainability. Consumerism is not sustainable without wealth, and global attitudes toward wealth, particularly corporate wealth, are synonymous with irresponsibility and negligence in conservation and stewardship toward planet Earth. Included in their research, students may consider this concept of “inspirational texts” that provide a foundation for living sustainably and share in their discussions and reflections such sources that reveal a renewed awareness of our human need to thrive with nature, not against it.

Instructions

Part 1. Reading the core text and introducing the topic of “Throwaway Living”

The lesson begins with students independently reading the core text Plastic Ocean Chapter: 6 “The Invention of Throwaway Living” by Captain Charles Moore with specific attention to historical events mentioned in the chapter. Central to this unit’s theme is Captain Moore’s reference to August 1, 1955 as “the birthday for the new age of disposability” (Moore 94) with the iconic photograph by Peter Stackpole with an article called, “Throwaway Living: Dozens of Disposable Housewares Eliminate the Chore of Cleaning Up” as presented in the August 1955 issue of LIFE Magazine. This reading generates connections to several additional texts and the gathering of research based on the historic events identified by Moore throughout the chapter. While reading Chapter 6 should be an independent practice for students, the additional texts may be divided among groups and each group may present their specific text to the class by identifying the connections they make with Chapter 6.

Part 2. Reading additional texts and conducting research into contemporary texts on throwaway living and counterculture

There is a lengthy timeline of material to identify in Chapter 6 which is intended to prompt students toward identifying specific events on a past timeline to then acknowledge items on a present-day timeline which leads toward a prediction for an end date to the age of disposability. Students will use small group discussion time to research, theorize, predict, debate, and determine these significant events and dates. Students will explore a variety of online articles which reference the August 1, 1955 LIFE article and image by Peter Stackpole to make comparisons between texts including the core text:

- The World Is Drowning in Plastic. Here’s How It All Started | WIRED

- The History of Plastic: The Invention of Throwaway Living | Dieline – Design, Branding & Packaging Inspiration (thedieline.com)

- Why our throwaway culture has to end | National Geographic

- This link to a short article by Dr. Ross Headifer also provides additional links for further research: ‘Throwaway Living’: When Tossing Out Everything Was All the Rage – Plastic Waste Solutions

- Students will extend their research by engaging with social media platforms that promote awareness about the plastic pollution crisis including Captain Moore and the Algalita research team on Instagram, @algalitacapnmoore and @algalita.

Also, consider incorporating one of the following hands-on activities to provide experiential learning in the research process:

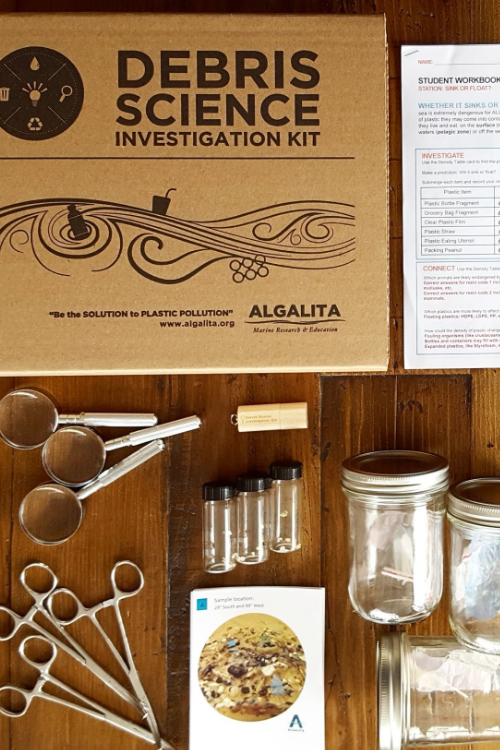

- Plastic Ocean Teaching Kit (A hands-on introduction to ocean plastics research)

- Can it be recycled? (Understand the reasons why some materials get recycled, and others don’t)

- Be a Greenwashing Detective (Investigate corporate greenwashing which relies on inaccurate information to encourage continued customer support and patronage)

Facilitation suggestions: Assign each group one or two additional texts to read, analyze, then present on. Students should include the key points from the article(s), connections to the core text, as well as related social media research to the entire class. Frequent small group discussions are necessary for this unit to allow for a variety of conversations, research, evidence, and theorizing to emerge among the students. Teachers may determine what works best for their classes in terms of dividing independent and group work. It will be important to provide clear expectations for students in terms of the rubric for independent assignments versus group assignments. Finding ways to engage all students in each group is also essential to the success of the group project. Asking students to keep an Independent Research Journal or Progress Chart to show their personal research that they bring to the Group Discussions may be the best way to encourage consistent participation.

Part 3. Independent or Group Timeline Creation

Students will work independently to compile information they gather with their groups into a Unit Project: “Two-Part Timeline: The Beginning of Throwaway Living and its Preconceived Endgame”

- Timeline Part I : will present significant events in the history of “Throwaway Living” from its beginning to present day as revealed by Captain Moore and other research.

- Timeline Part II: will explore ways to forecast the end of “Throwaway Living” and anticipate Captain’s Moore’s vision for a “preconceived endgame” (page 108) as the rule, instead of the exception for plastic items and packaging. Students will anticipate and hypothesize future results based on what actions are presently occurring and need to continue to end the plastic pollution crisis with a specific anticipated date and year. This projection will challenge students to theorize and determine how long it will take to reverse the damage that started on August 1, 1955, based on present day conveniences, plastic excess, corporate greenwashing, and the global pollution crisis.

Timeline format suggestions: Materials and medium for timelines include long sheets of rolled paper, or digital timelines, or a combination of written and digital. It will be important to clarify the options open to students, supplies and materials available, and expectations for what is to be included.

Facilitation suggestions: There are a variety of ways to approach the Timeline Part I and Part II. Teachers may create a list of the historical events in Chapter 6 and ask students to select 5-10 events to research for their timeline, or teachers may ask the groups to make lists of all the events in Chapter 6 to determine which ones received the most attention through their reading. Encourage collaboration and reflection with daily opportunities to share their group progress with the class.

Part 4. Independent or Group Presentations

Students will share their completed Unit Project: Timeline Parts I and II as presentations to the whole class. If the option exists for students to post pictures of their project in a school-provided online digital platform, this is highly recommended as students may view each other’s work digitally in an online gallery format which also provides the option to project each timeline on a screen in addition to displaying hardcopies. If there is an opportunity for students to showcase this project in a larger setting: all-school assembly, school art-show, or other venue that extends the discussion of conservation activism to a larger community, this is an exciting opportunity to equip students with career-based experience. If possible, community members, legislators, representatives, and members of the press may also be invited to view student projects and learn about their research.

Part 5. Independent Reflective Writing

Students will engage in reflective writing about the entire project process with a conclusion focused on their perspective and thoughts on the “end of the destructive mindset of throwaway living.” Each student should reflect and write about:

- their process reading, researching, gathering data, comparing and connecting the texts,

- the process of collecting specific dates for significant events to include on a timeline,

- debating and discussing results,

- theorizing and predicting a “preconceived endgame,”

- and presenting the timelines.

Students should also elaborate on what inspirational texts motivate their own activism based on Moore’s statement on page 97 and how they anticipate their own choices about the plastic pollution crisis may lead toward change for a cleaner and healthier future.

Facilitation suggestions: Regardless of how they created their timelines, either independently or as groups, the reflective process should be thoughtfully considered by students individually.

Tips and Suggestions

This lesson plan is flexible and may work best with multiple departments and a commitment to cross-curricular activities ranging from reading, analyzing data, gathering historical events to present on a timeline, identifying current events and influencers on a timeline that predicts the future, and writing reflectively. Depending on time, however, one department, such as Language Arts could successfully engage in this unit opportunity for current event exploration and research.

Reflective Writing is essential to the writing process and may occur throughout the Unit but may be most effective at the end of the Unit Project as students consider what they did, what they tried, what worked, what could be improved, and how the project has increased their awareness in some way. Teachers may review sample suggestions for reflective writing, including 10 Unique and Creative Reflection Techniques & Lessons for the Secondary Student — TeachWriting.org

Teachers may provide students with sample timelines to model the Unit Project, some suggestions are

Encouraging students to engage with social media sites will add important layers of discussion to this unit. Digital Discussion Boards provide a classroom platform for posting websites and Instagram sites where students may share with the entire class what they are learning in real time from present day environmental activists. Teachers may also share a list of sites to start the process. Students may respectfully comment on sites where they are gaining useful information research for their projects. This will be especially useful for Timeline Part II in which students will consider the current realm of environmental awareness as they discern who is taking an active role in the process to end the plastic pollution crisis.

An example of extended research and sample timeline which Captain Moore references regarding the historic change from reusable milk bottles to disposable cartons is in Chapter 6, page 101: Wades Dairy Farm in Bridgeport, CT Wade’s History & Timeline l Wade’s Dairy Since 1893 (wadesdairy.com)

Associated Standards

NCTE/IRA Standards for the English Language Arts

- Students read a wide range of print and nonprint texts to build an understanding of texts, of themselves, and of the cultures of the United States and the world; to acquire new information; to respond to the needs and demands of society and the workplace; and for personal fulfillment. Among these texts are fiction and nonfiction, classic and contemporary works.

- Students read a wide range of literature from many periods in many genres to build an understanding of the many dimensions (e.g., philosophical, ethical, aesthetic) of human experience.

- Students apply a wide range of strategies to comprehend, interpret, evaluate, and appreciate texts. They draw on their prior experience, their interactions with other readers and writers, their knowledge of word meaning and of other texts, their word identification strategies, and their understanding of textual features (e.g., sound-letter correspondence, sentence structure, context, graphics).

- Students adjust their use of spoken, written, and visual language (e.g., conventions, style, vocabulary) to communicate effectively with a variety of audiences and for different purposes.

- Students employ a wide range of strategies as they write and use different writing process elements appropriately to communicate with different audiences for a variety of purposes.

- Students apply knowledge of language structure, language conventions (e.g., spelling and punctuation), media techniques, figurative language, and genre to create, critique, and discuss print and nonprint texts.

- Students conduct research on issues and interests by generating ideas and questions, and by posing problems. They gather, evaluate, and synthesize data from a variety of sources (e.g., print and nonprint texts, artifacts, people) to communicate their discoveries in ways that suit their purpose and audience.

Did you use this lesson?

Help us track our reach

Related Resources

Lesson: Plastic Soup in a Brave New World

Compare themes between two texts, Plastic Ocean Chapter 1 by Charles Moore, and The Tempest by William Shakespeare and create maps to present the similarities and differences between the two storylines.

Grades 10 and up

3 weeks

"Plastic Ocean" English Language Arts Toolkit

Research, comprehend, discuss, and communicate about the problem of plastic pollution and solutions to this global challenge through a literary lens.

Grades 9 and up

Variable Timing

Lesson: Can it be recycled?

Find out why less than 10% of plastic gets recycled globally and what we can do about it.

Grades 5 and up

60 to 90 minutes

Toolkit: A Plastic Ocean Teaching Kit

Investigate the impacts of microplastics on our oceans with 3 rotating activities.

Grades 5 and up

50 minutes

Be a Greenwashing Detective

Learn about a strategy companies use to maximize profit through deceiving marketing.